81 How did this many absences become normal?

Laura Tilghman

Spring 2022

Originally posted on lauramtilghman.plymouthcreate.net on May 7, 2022

Students absent from class. Retired faculty absent from our campus community. And an Ed Yong fangirl moment.

This semester I taught a course called “Illness, Wellness, and Healing.” It is a core course in the Global Health minor as well as a combined WECO/INCO course in the General Education program, so it tends to draw students from across campus. I hope that students will leave with an understanding of how people’s behavior, beliefs, and experiences of illness and wellness are profoundly shaped by the society and culture that they are a part of, which in turn influences the healing processes that they identify and use.

I was also teaching this course when the pandemic first started in spring 2020. I actually used news footage of a “new mysterious virus” as fodder for a first day exercise, having students pose questions that they had about this topic and then trying to guess what anthropologists and sociologists might ask about it. (Most students in the course are from other majors – nursing, social work, public health, and so on – so I was hoping to get them thinking about what sorts of questions their disciplines ask about the world, and how these might differ from anthropology and sociology.) Only a couple students had even heard about covid-19 at that point.

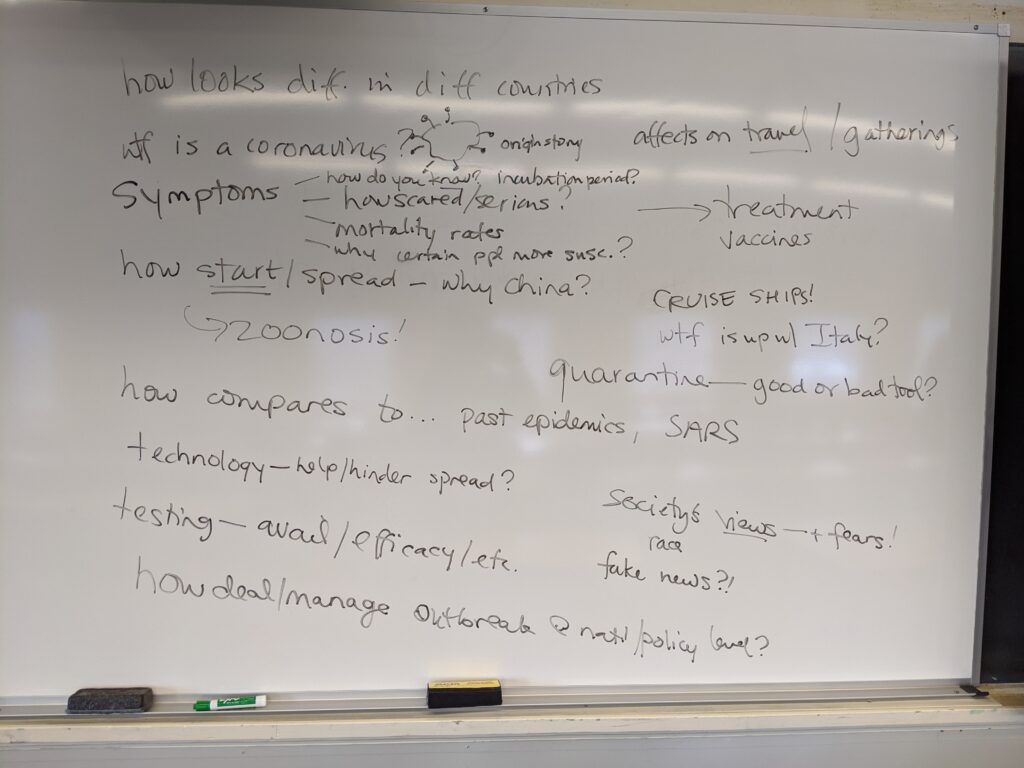

Later, just before spring break when news of the virus was becoming more widespread but still far off from rural New Hampshire, students voted as a class to shift some of our readings in the second half of the course to cover this topic. We brainstormed questions (see below) and I started vacation browsing new readings and videos.

You all know what comes next: pandemic declaration, lockdowns, emergency remote instruction. What had seemed like an interesting intellectual pursuit completely upended my life and the lives of all my students. We still learned about the pandemic through an anthropological and sociological lens, but doing so was much heavier and personal than any of us had anticipated.

When I went to teach the course again this semester, I wondered how much time to devote to the pandemic in course materials. When I surveyed students, their responses really ran the gamut. Some were eager to learn more about the pandemic in a scholarly and in-depth way, in contrast to soundbites on social media. Others were understandably over it, either because other classes had also covered it, or because it had personally impacted them so negatively. Who wants to relieve the trauma of illness, loss, unemployment, loneliness, missed proms and graduations

So in the end, we just spent a week discussing new and re-emerging diseases, of which COVID-19 is just one of many that are becoming more common as humans encroach into animal habitats and change the climate.

One article that unfortunately did not make the cut when I was designing this part of the course was Ed Yong’s haunting piece “How Did This Many Deaths Become Normal?” The article was written as the US approached the grim milestone of 1 million deaths due to COVID-19, and tries to investigate the lack of individual and collective mourning and reckoning of loss at such a huge scale.

In trying to reflect upon my experience with the CPLC and what it felt like to teach this academic year, I kept thinking about Ed Yong’s article. I have heard from many professors a concern about high absences and low engagement this semester – expressed in conversations in the hallways at PSU, in tweets, and in articles in the Chronicle and IHE. I believe that embedded in this concern is a hidden wish that our students learned and lived as they did pre-March 2020. I think we all know that students are not as engaged as they once were because the pandemic is ongoing no matter how much we wish we could will it away. But equally important for explaining student disengagement this academic year is the toll it takes on people to live and learn without a reckoning of what has been (and continues to be) lost.

Yong discusses the experience that many feel of not having the opportunity to recognize the huge impact of the pandemic, writing that some people “are grieving raw and recent losses, their grief trampled amid the stampede toward normal.” He then quotes Steven Thrasher as saying, “We’re not giving people the space individually or societally to mourn this huge thing that’s happened.”

Whether it is faculty or administration, or students themselves, we have tried to leapfrog this important step of wallowing in what the pandemic wrought before being able to return to normal, or make a new normal. But our brains and hearts won’t let us move past it, and this results in learning and teaching challenges like “disengagement” or absences.

Yong also writes that, “Many aspects of the pandemic work against a social reckoning.” He writes about the difficulty of coming to grips with the impact of a virus that is itself invisible to the naked eye and whose victims are often hidden away in hospitals, nursing homes, or prisons. This contrasts with the unignorable burned out husk of a building (9/11) or flooded streets (Hurricane Katrina), tragedies that we have done a much better job of memorializing.

Likewise, there are aspects of a higher education that make it difficult to have a social reckoning regarding the impact of the pandemic on the campus community. Students are transitory, spending just 4+ years with us. Faculty are for the most part left to their own devises to design and teach their courses (though CPLC has done an excellent job of creating community and reasons for gathering!) We don’t really come together as a whole campus community ever, perhaps save for commencement. As a result, opportunities to even fully see the pandemic’s impact on our campus, much less to grieve and commemorate it, are limited.

Concurrent with the pandemic, our PSU campus went through several academic and administrative changes. Program curtailment meant getting rid of several small majors, including my own. Budget issues prompted the university system to offer early retirement packages, which over 30 faculty took. A dozen more left for other reasons. Small changes perhaps for some people from other vantage points, but for me it has completely altered my work identity and job responsibilities.

Now, I spend my commute listening to podcasts instead of talking shop about classes since my carpool buddy retired. I arrive late morning but am guaranteed to find an open parking spot in front of my building. All that is left of two colleagues that I used to share a hallway with are some discarded textbooks and old VHS tapes on a bookshelf. I think my job title is still “associate professor of anthropology” but there is no longer an anthropology major. Like I said, disorienting. But just as our campus has not really reckoned with or memorialized the impact of the pandemic, we have also failed to do so for program curtailment and a large swath of faculty retiring.

This is not to say that the future is grim! I have many things I am looking forward to starting in 2022-2023. I was part of a group who collaborated in designing the new Sustainability Studies major, which was recently voted into being by the entire faculty. I am so excited to teach one of the new core courses we designed for it next year! I am part of the inaugural HoME (Habits of Mind Experience) group, made of up of faculty who have chosen to redesignate partially or wholly with the General Education program and reorient some or all of their teaching, service, and scholarship. I left our first HoME meeting so appreciative of these thoughtful people that I get to work with.

But: I am still grieving all that was lost and changed these past two years– at both a planetary and campus scale – and am searching for ways to commemorate these absences. I don’t know how we rebuild without this necessary step.

Feedback/Errata